When the year comes to an end and the first snowflakes start to fall, the most awaited winter ritual in Canada, apart from drinking hot chocolate or chasing a puck on frozen lakes, is hitting the slopes for skiing! This outdoor activity that comes with snow, especially in Vancouver, can make the winter months for us avid riders much more bearable. Unfortunately, pain can often stop us from taking to the slopes.

At the beginning of each ski season it’s pretty much a given that most of us will be moaning and dealing with pain and discomfort the first couple of days on the slopes. Unfortunately, for some of us pain will become a standard part of our weekly activity for the whole season and for a few of us pain can be unbearable and will stop us from skiing.

In this article I will summarize not only some of ache and pain types I have encountered myself since I was 18 when I started my first teaching season and ,, was forced,, to spend most of the day in ski or snowboard boots, but also what I have learned from helping my clients to get back on track.

Pain is not always your enemy

Pain is not always your enemy

As a therapist who treats many people with ski injuries, I have witnessed many who consider pain to be their enemy.

It is more than clear that none of us are not big fans of pain. However, it is one of the body’s most important communication tools. Imagine what would happen if you felt nothing when you stepped on a sharp nail.

Pain is one way the body tells you something is wrong and needs attention.

It is up to the brain to decide what kind of message it gives to us at any particular moment. However, all pain has a message of some kind, whether related to a physical condition, such as a broken arm or torn ALC ligament, or related to a psychological situation. While many of us begin to feel that our brain has betrayed us by giving us such pain, it is actually trying to protect us from what the brain perceives to be a dangerous situation in our body.

Understanding our pain requires a change in perspective. As I mentioned before, pain helps us to protect. It tells us “Don’t do it!” when we try to hit a jump in the snow park because of a broken a leg injury years ago when jumping from a wall. It is guiding us through the world. Instead of thinking of pain as the enemy, it may be helpful to start thinking of it as a friend. But, like a protective friend, pain can also warn us of these potential hazards before we injure ourselves. Pain processing occurs in the brain, and our body has the ability to recall things that have caused pain in the past, so it can clue us in to possible dangers.

The nervous system has a remarkable ability to adapt, and it can quickly go from our cautious friend to a prison guard who won’t even let us go skiing. So how do we get our pain processing to re-calibrate and behave more like a helpful friend? Simply start educating yourself about pain physiology. It should be the first and most helpful step towards improving your relationship with pain. Studies have found that learning about pain reduces pain and disability- so even just reading about how pain works can help you manage your symptoms.

Things you should know about pain

Things you should know about pain

Pain does not originate from the tissue of our body, but it is output from our brain. Our brain communicates with tissues of our body and serves as a defense against possible injury or disease.

The degree of injury does not always have to equal the degree of pain. We all experience pain in individual ways. Pain can be influenced by many factors, such as anxiety, stress and depression. Our social environment such as work or stressful situations may influence our perception of pain. Women often feel more pain than men because of conditions and experiences such as menstruation, childbirth and migraines.

Back pain is the most common pain condition according to the National Institutes of Health. A combination of gentle, regular stretching and strengthening exercises, as well as reaching and maintaining a healthy body weight, can make a real difference.

Pain types and classifications

It is well known among both skiers and snowboarders that after a long day of riding in deep fresh powder our muscles get more sore than cruising on groomed slopes. We all know that burning sensation in our legs.

Fatigue after good, strenuous physical activity is a sign that the exercise is pushing the limits of our physiology. As long as it leaves us exhilarated but

not overly exhausted, we know that we are using our muscles correctly. But if fatigue lasts more than a few days, it usually means that our physiology has been excessively challenged and our muscles and the energy stores were not being effectively replenished. Chronic fatigue after excessive exercise suggests that the individual may be overtraining. If after appropriate rest the fatigue continues, it may be a sign of other medical problems and we should seek out medical help.

Acute and chronic pain

Acute pain is the most common type of pain, usually associated with small injuries like muscle strains or ankle sprains which are frequently caused by damage to tissue such as bone, muscle or organs. Acute pain occurs suddenly and usually goes away as you heal. If not appropriately treated, acute pain can turn into chronic pain. The duration of acute pain is less than three months and responsive to many treatments such as physical therapy, osteopathy, chiropractic treatments or massage therapy depending on the root of the problem.

If your pain lasts more than three months, it is considered chronic pain, and you may require help from a medical doctor to understand the cause and determine treatment. Chronic pain can be a result of damaged tissue. Often is associated with nerve damage. A variety of syndromes and conditions can cause chronic pain. It is essential to identify the root of the pain, as well as manage the pain itself. Different conditions require different types of treatment. Chronic pain can last for years. The most common conditions are lower back pain, arthritis pain or as mentioned above, pain caused by nerve damaged. It can cause tense muscles, problems with moving, a lack of energy, and changes in appetite. It can also affect your emotions. Some people may feel depressed, angry, or anxious about the pain and the injury coming back. My suggestion is not to rely only on medicine as it can lead to addiction and other serious side effects. Besides visiting physiotherapists, manual osteopaths or chiropractors, proper exercises, rest and even meditation can help with self- regulation of the pain symptoms.

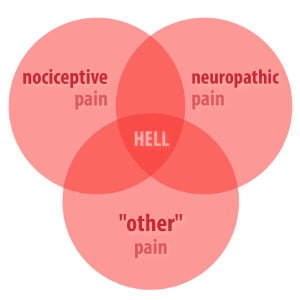

Nociceptive and neuropathic pain

Most pain that comes from tissue damage is nociceptive pain. It arises from an injury to the body’s tissues – bone, muscle or organs. With this type of injury you may experience an ache, a sharp stabbing or a throbbing. It usually comes and goes but it can also be constant. You may feel the pain worsen when moving, laughing or deep breathing. Pain from tissue damage can be acute. For example, ski injuries like a sprained ankle or a skier’s thumb are often the result of damage to soft tissue. Or it can be chronic, such as arthritis or chronic headaches. It tends to go away as the affected body part heals.

Neuropathic pain is a medical term used to describe the pain that develops when the nervous system is damaged or not working properly due to disease or injury. Symptoms often described as a shooting, burning, tingling, numbness or sensitivity to touch can go away on its own but most of the time is chronic. It often is the result of nerve damage or a malfunctioning nervous system. The impact of nerve damage is a change in nerve function both at the site of the injury and areas around it.

Skiers and snowboarders can develop this nerve dysfunction on the slopes by head injury/trauma, disc herniation or repetitive stress injury. Amongst other factors can be diabetes, tumors, infections or genetic.

How to reduce pain while skiing and snowboarding

There is no question that skiing is a sport with some inherent risk but it is important not to lose sight of how much joy you can get from riding with your friends or family. There are many articles about ski injury prevention. This time I decided to add a few tips on what to do when we are already carving groomed slopes or fresh West Coast powder to minimize the risks of getting injured.

Always take one warm-up run down the easiest hill each time

before hitting more advanced terrain. Trauma happens to muscles when they are shocked too fast by a challenging activity.

Shake it off. After you complete a run, jiggle your quads by shaking your legs to get them to unclench. This is called vibration training, and it can help you prevent soreness between runs.

Your decision to stretch or not to stretch should be based on what you want to achieve. If the objective is to reduce injury, stretching before exercise is not helpful, according to Dr. Shrier (2007). Do not waste your time with too much stretching before skiing. Your time would be better spent by warming up your muscles with light aerobic movements and gradually increasing their intensity.

Keep hydrated. Losing water through sweating has been shown to decrease muscle strength. Consuming water, on the other hand, helps your body build new muscle tissue. So to keep your muscles strong – which can help you maintain proper posture and limit the risk of pain, we should drink about 17 ounces of water two hours before exercise, then at regular intervals during exercise to replace lost fluids.

After you finish riding, stretching and ice would be your best choice. Skiing can often result in delayed onset muscle soreness, which results from small tears in the muscle during physical activity and causes muscle inflammation (McNamara, 2015). Elevating your legs can prevent inflammation. Intense blood flow to a sore area, known as edema, is part of the pain of soreness. Raising your legs above your heart will slow the blood that is rushing to fix your muscles.

If still feeling sore muscles three days after skiing, perform light exercise with them. The exercise will bring oxygen to the sore muscles and help to destroy the lactic acid that is causing you pain.

Bibliography

- Shrier I. “Does stretching help prevent injuries?”, 2007

- Allegri M, Montella S, Salici F, et al. “Mechanisms of low back pain: a guide for diagnosis and therapy”, 2016

- Kosek E, Cohen M, Baron R, et al. “Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states?”, 2016

- McNamara, Melissa. “How to Get Rid of Sore Legs from Skiing.” November 15, 2015

- https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/chronic-low-back-pain-research-standards-announced-nih-task-force

- https://www.webmd.com/pain-management/pain-management#1

- https://www.painscience.com/articles/pain-types.php

Pain is not always your enemy

Pain is not always your enemy Things you should know about pain

Things you should know about pain